This is part one of a two part series discussing laws that regulate the tobacco industry and pigovian taxes: excise taxes placed on a market to correct a market outcome, often because of a negative externality such as health risk or pollution.

The Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act is a newly-enacted federal law that gives the FDA regulatory power over the tobacco industry, among other provisions that attempt to dissuade misleading advertisement on young and old smokers alike. The law was signed into effect on June 22, 2009.

There were two major advertising provisions contained in the law. The first was that over 50% of the front and back of every cigarette pack must be warnings with a giant ‘WARNING’ in capital letters . The second, and maybe more important, is the banning of the use of words ‘light’, ‘mild’ or ‘low’.

From a policy standpoint, it seems the second, but not the first, may be useful. Let us address the first provision. Armed with anecdotal evidence, it seems difficult to believe that there are people out there who feel that cigarettes are not in some way bad for one’s health. True, there is a great variance on the degree to which people feel cigarettes are bad. The key to unearthing the efficacy of the bill, however, is to look at the smokers on the margin. Will there be any smokers out there, who look at the new ‘WARNING’ signs and then decides that since the warning signs are now larger on the package they will now stop or cut back smoking? I tend to think not. The major effect of this bill will be simply to shift the way the cigarette companies print out their packaging.

The second provision mentioned above, addressing the use of ‘light’, ‘low’, and ‘mild’ is slightly more interesting. There is substantial evidence (here) that these ‘light’ cigarettes are no different for the health of smokers than other more traditionally packaged cigarettes. For example, smokers tend to smoke to get the right amount of nicotine and if ‘light’ cigarettes siphons off any, many smokers will substitute out into deeper breaths, more cigarettes or smoking more of the cigarette. The benefit of this is more to the point of dispelling the oft-believed idea that ‘light’ cigarettes are better for one’s health than other traditional cigarettes.

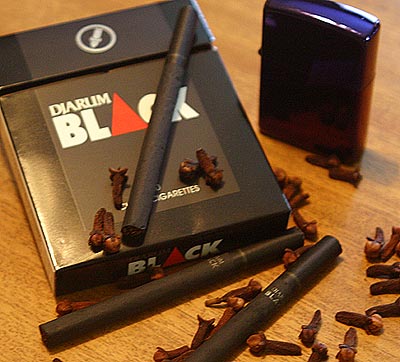

Now, let me address another important provision of the bill, and the politics behind this specific issue and the entire cigarette debate. This part of the bill prohibits use of flavors in cigarettes that includes clove, cinnamon, candy and fruit-flavored cigarettes. Notably absent from this ban is the most popular flavored cigarette in the country, menthol cigarettes.

- Clove cigarettes, such as these, are illegal under the new law. (from Wikipedia)

The lion’s share of clove cigarettes, or kretek, are imported from Indonesia. Tobacco cultivation has a very prominent role in the history of the American economy and the foundation of our country. In this way, a lot of the politics over the history of the cigarette debate has centered on treating cigarette farmers in the same regard as wheat and corn farmers, and the argument is fairly valid. Do corn farmers get a hard time from legislators for high fructose corn syrup that has been linked to diabetes development and heart disease? I am not suggesting that they should, but the farmers themselves have a tough draw, and this can be seen in the states that vote for and against cigarette regulation. North Carolina, Virginia, South Carolina are traditionally the center of the cigarette as cash crop region in America. Thus, these states would not be opposed at all to the prevention of foreign competition (such as Indonesian clove cigarettes). As will be discussed in a later article by me, this temptation to prevent foreign competitions only hurts the consumers that are dependent on these goods, but that is for another time. Next article will be on the specific policy decisions of policy makers in dissuading cigarette usage and its efficacy.

Cheers,

Cameron Daniels

(Keep reading! For part 2, click here.)